Gasteruptiinae

Gasteruption

John T. Jennings and Andrew R. DeansIntroduction

Gasteruptiinae is represented by the nominal, speciose genus Gasteruption Linnaeus with about 400 described species. It is cosmopolitan in distribution (Kieffer 1912; Crosskey 1962), though unknown from Polynesia and Hawaii (Crosskey 1962), and it is apparently most diverse in the Australian and Ethiopian regions.

Characteristics

Several characters distinguish Gasteruptiinae from their sister subfamily, Hyptiogastrinae:

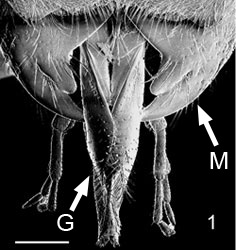

- Mandibles are short and not broadly overlapping when in the closed position (Fig. 1)

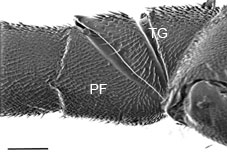

- The prefemur is generally present (Fig. 2 PF), though sometimes indicated by a slightly differentiated basal swelling

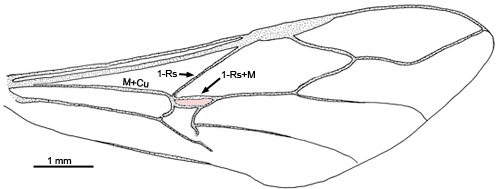

- forewing 1-Rs+M connects directly to the intersection of the M+Cu and 1-Rs, with the first discal cell (in pink) posterior to the 1-Rs+M and M+Cu connection (see Fig. 3) (some species have a triangular first discal cell)

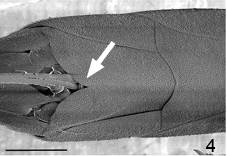

- Female subgenital sternite is notched or a slit (Fig. 4)

- Hind trochanter has a a groove (Fig. 2 TG)

- The ovipositor is long (at least 0.5 length of metasoma; see title figure above)

Figs.1-2 Gasteruption characters. (1) mouthparts with non-overlapping mandibles, with mandibles (M) and galeae (G), scale=500um; (2) hind trochanter with trochanteral groove (TG) and prefemur (PF), scale=100 um

Fig. 3 Gasteruption sp. wing venation, first discal cell in pink.

Fig. 4 Gasteruption sp. subgenital plate with notch; scale=500 um.

Discussion of Phylogenetic Relationships

The taxonomy of Gasteruption has been partially revised in a series of papers by Pasteels (1957a,b, 1958a,b, 1962), but these studies were undertaken prior to the widespread use of mass collecting techniques (e.g., Malaise and yellow pantraps). Hence, many collections now contain a large amount of new material including many new species. There are no published estimates regarding the relationships between species, and there are no recent comprehensive keys to spp.

Biology and Host Relationships

Early records indicated that twig-nesting species of solitary bees (e.g. Ceratina, Heriades and Hylaeus) were the only hosts for Gasteruption (Höppner 1904; Rau 1928). More recent and extensive records indicate that a much wider range of solitary bees and wasps act as hosts for this genus including the Anthophoridae, Colletidae, Megachilidae, Sphecidae, and Vespidae (Masarinae) (Jennings and Austin 2004). Available data also suggest that individual Gasteruption species vary from being polyphagous to having a more restricted host range. For example, the European species G. assectator F. and G. jaculator (L.), apparently have a wide host range (Colletidae, Megachilidae, Sphecidae and Vespidae), while others such as G. caudatum Szépligeti and G. freyi (Tournier) are recorded as parasitising only Megachilidae and Colletidae, respectively. However, these data are based on a restricted number of records and should therefore be treated with caution.

Upon detecting a potential host nest, the female wasp will hover around and antennate on the entrance (Morley 1916). She will then repeatedly settle and thrust the full length of the ovipositor into the nest while the valves remain at right angles to the trunk. In the case of an already sealed nest, the wasp pierces it by pushing without any drilling action. Gasteruptiids do not have grooves on the hind coxae to guide the ovipositor like their probable sister family, Aulacidae.

Different species of Gasteruption deposit their eggs in proximity to the host egg, with the exact positioning depending on the species (Malyshev 1964, 1966). Some species are ectoparasitic, in that they lay their eggs on the egg of the host bee or wasp. Other species lay their eggs on the store of honey just in front of the host egg, on the wall of the cell in front of the food store, or on the outer surface of the cell lining. Höppner (1904) reported that G. assectator is ectoparasitic on Hylaeus spp. and actually oviposits onto the mature host larva.

There are considerable differences among species in the exact method of parasitism, with the larvae of some species consuming the host egg and others consuming the host larvae. For example, shortly after hatching, the larvae of G. caudatum and G. pyrenaicus consume the host egg (Malyshev 1966). The second instar larvae of these two species then feed on the food store of the host bee. In some cases the larva completes its development by consuming the food store in more than one cell: if the partitions are weak or brittle, the larva may invade surrounding cells where it consumes both bee larvae and food stores. In comparison, the larva of G. assectator consumes a mature Hylaeus larva upon eclosion (Höppner 1904); it then invades a second cell and consumes that larva also.

Information regarding pupation in Gasteruption is very scarce. The larva of G. robustum pupates at the end of the tunnel of the host bee where it seals itself off with a tough partition constructed from an anal excretion (Whatmough 1974). Gasteruption caffrarium pupates inside two cells of Hylaeus (Skaife 1953), while G. assectator pupates in a cocoon within the cell of its host (Crosskey 1951). Pupation within the host cell has also been observed in Australia for several Gasteruption spp. (Jennings and Austin, unpublished).

Adult Feeding and Phenology

Gasteruption have elongate glossae (Fig. 1), typical of nectar feeding wasps. The galeae are flattened and foliaceous with a fringe of stout comb-like setae on the inner margin (the galeal pecten), the fused glossae (the glossa sensu Crosskey) are well developed, and paraglossae reduced (Crosskey 1951). Examination of the mouthparts of a range of Gasteruption spp. revealed pollen on approximately one-third of individuals, although the load varied considerably with species (Jennings and Austin unpublished). Given the range of plants visited that produce both pollen and nectar, it is likely that at least some Gasteruption feed on both nectar and pollen (Jennings and Austin 2004).

Although data for most regions are either scarce or non-existent, adult Gasteruption have been recorded as visiting a wide range of flowers from many species and families. Apiaceae appear to be favoured by Gasteruption in the Palaearctic region and Myrtaceae in the Australian region. This family is dominant in the Australian flora with over 1500 species and it is therefore not surprising that Gasteruption have been widely recorded as visiting this plant group. Myrtaceae visited by Gasteruption include Angophora, Eucalyptus, Leptospermum, Lophostemon, and Melaleuca (Jennings and Austin 2004). These genera produce both pollen and nectar in large quantities and are visited by many groups of insects. Other plants visited such as Schinus (Anacardiaceae), Banksia and Grevillea (Proteaceae), and Atalya (Sapindaceae) also produce both pollen and nectar.

Gasteruption caffrarium is multivoltine with two or three generations occurring each year in southern Africa (Skaife 1953). Collection data for other Gasteruption indicate that in North America, G. assectator are collected between late April to early Oct., with the peak in late May, whereas G. pattersonae Melander & Brues are collected from late April to mid September (Townes 1950).

References

Crosskey, R. W. 1962. The classification of the Gasteruptiidae (Hymenoptera). Transactions of the Royal Entomological Society, London 114, 377-402.

Höppner, H. 1904. Zur Biologie der Rubus-Bewohner. Allegemeine Zeitschrift fur Entomologie 5/6, 97-103.

Jennings, J. T. and Austin, A. D. 2004. Biology and host relationships of aulacid and gasteruptiid wasps (Hymenoptera: Evanioidea): a review. pp. 187-215. In Rajmohana, K., Sudheer, K., Girish Kumar, P., & Santhosh, S. (Eds.) Perspectives on Biosystematics and Biodiversity. University of Calicut, Kerala, India.

Kieffer, J. J. 1912. Evaniidae. Das Tierreich 30, 1-431.

Malyshev, S. I. 1964. A comparative study of the life and development of primitive gasteruptiid - Ichneumon-flies (Hymenoptera). Revue d'Entomologie de I'URSS, 93, 524-534.

Malyshev, S. I. 1966. Genesis of the Hymenoptera and the Phases of Their Evolution. (Transl.) (Methuen & Co.: London).

Morley, C. 1916. Garden notes. Entomologist 49, 246-248.

Pasteels, J. J. 1956. Hymenoptera : Gasteruptionidae. pp.483-484. In Hanstrom, B., Brinck, P. and Rudebeck, G. (Eds.), South African Animal Life. Results of the Lund University Expedition in 1950-1951 Vol 6. (Alnqvist and Wiksell: Stockholm).

Pasteels, J. J. 1957a. Revision du genre Gasteruption (Hymenoptera, Evanoidea, Gasteruptionidae). Espèces australiennes. Memoires Institut Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique 56, 1-125.

Pasteels, J. J. 1957b. Révision du genre Gasteruption (Hymenoptera, Evanoidea, Gasteruptionidae). III Espèces néozélandaises. Bulletin et Annales de la Société Royale Entomologique de Belgique 93, 173-176.

Pasteels, J. J. 1958a. Trois nouveaux Gasteruption Hymenoptera, Evanoidea, Gasteruptionidae) d'Afrique occidentale. Bulletin et Annales de la Société Royale Entomologique de Belgique 94, 125-128.

Pasteels, J. J. 1958b. Révision du genre Gasteruption Hymenoptera, Evanoidea, Gasteruptionidae), V. Espèces indo-malaises. Bulletin et Annales de la Société Royale Entomologique de Belgique 94, 169-213.

Pasteels, J. J. 1962. Espèces peu connues on nouvelles du genrs Gasteruption, en provenance de l'Afrique noire (Hymenoptera, Evanoidea). Bulletin et Annales de la Société Royale Entomologique de Belgique 98, 49-60.

Prinsloo, G. L. 1985. Order Hymenoptera (sawflies, wasps, bees, ants). Suborder Apocrita. Section Parasitica. pp. 404-406. In Scholtz, C. H., and Holm, E. (Eds.), Insects of Southern Africa (Butterworths: Durban).

Rau, P. 1928. The nesting habits of the little carpenter bee, Ceratina calcarata. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 21, 380-397.

Skaife, S. H. 1953. African Insect Life. (Longmans Green: Capetown).

Skaife, S. H. 1979. African Insect Life. Revised Ed. (Struik: Capetown).

Townes, H. K. 1950. The Nearctic species of Gasteruptiidae (Hymenoptera). Proceedings of the U. S. National Museum 100, 85-145.

Whatmough, R. H. 1974. Biology and behaviour of carpenter bees in southern Africa. Journal of the Entomological Society of Southern Africa 37, 261-281.

Title Illustrations

| Scientific Name | Gasteruption jaculator |

|---|---|

| Location | Europe |

| Specimen Condition | Live Specimen |

| Behavior | feeding |

| Sex | Female |

| Life Cycle Stage | adult |

| Copyright | © 2004 Hania Arentsen and Hans Arentsen |

About This Page

John T. Jennings

University of Adelaide, Glen Osmond, South Australia, Australia

Andrew R. Deans

Department of Entomology, NC State University

Correspondence regarding this page should be directed to John T. Jennings at

john.jennings@adelaide.edu.au

and Andrew R. Deans at

adeans@gmail.com

Page copyright © 2004 John T. Jennings and Andrew R. Deans

Page: Tree of Life

Gasteruptiinae. Gasteruption.

Authored by

John T. Jennings and Andrew R. Deans.

The TEXT of this page is licensed under the

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike License - Version 3.0. Note that images and other media

featured on this page are each governed by their own license, and they may or may not be available

for reuse. Click on an image or a media link to access the media data window, which provides the

relevant licensing information. For the general terms and conditions of ToL material reuse and

redistribution, please see the Tree of Life Copyright

Policies.

Page: Tree of Life

Gasteruptiinae. Gasteruption.

Authored by

John T. Jennings and Andrew R. Deans.

The TEXT of this page is licensed under the

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike License - Version 3.0. Note that images and other media

featured on this page are each governed by their own license, and they may or may not be available

for reuse. Click on an image or a media link to access the media data window, which provides the

relevant licensing information. For the general terms and conditions of ToL material reuse and

redistribution, please see the Tree of Life Copyright

Policies.

- First online 06 May 2005

Citing this page:

Jennings, John T. and Andrew R. Deans. 2005. Gasteruptiinae. Gasteruption. Version 06 May 2005. http://tolweb.org/Gasteruption/25832/2005.05.06 in The Tree of Life Web Project, http://tolweb.org/

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site

Go to quick links

Go to quick search

Go to navigation for this section of the ToL site

Go to detailed links for the ToL site